Thank God this happened in Georgia and not Minnesota.

Although I have a great deal of empathy for judges that have to deal with disruptive defendants, the following exchange between Judge and defendant is a glaring example of what can happen when a judge fails to maintain a sense of order and integrity in his/her courtroom. The end result is a ridiculous courtroom incident creating the perception of a judicial system with “out of control” courtrooms, run by “out of control” judges incapable of dealing with “out of control” defendants in a professional manner.

As you read and/or listen to the following outrageous courtroom exchange, ask yourself this question:

In order to maintain control in the courtroom and a sense of judicial dignity, at what point in the following exchange should the judge have STOPPED engaging the defendant, entered a finding of contempt and immediately ordered removal of defendant from the courtroom? First, a little background:

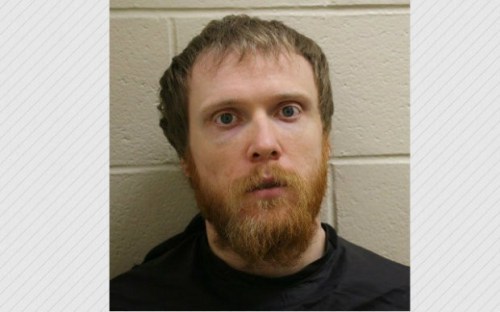

On June 20, 20126, alleged murderer Denver Allen and the Honorable Judge Bryant Durham decided to act out a more profane version of that scene between Principal Vernon and John Bender from one of my all time favorite movies, “The Breakfast Club” in a Georgia Courtroom.

Defendant Allen, accused of committing a deadly jailhouse assault last year, appeared in court seeking to represent himself, claiming his public defender said he would only do “a good job” if he was allowed to give Defendant Allen oral sex. Judge Durham advised him against it. Things quickly went downhill from there.

The prospect of spending significant time in contempt of court didn’t deter Defendant Allen from demanding that the judge suck his “donkey” dick. They say that the most dangerous man is one with nothing less to lose. Allen is already going on trial for killing a man, what’s contempt of court on top of a lengthy prison sentence?

According to the official court transcript what followed was a lengthy exchange in which Allen bragged about his “big old donkey dick” and his fondness for “white boys with big butts” while repeatedly commanding Judge Durham to suck said donkey dick.

In return, an alternately smiling and red-faced Judge Durham said Allen “looked like a queer” and speculated that “everybody [must enjoy] sucking your cock” but insisted his mouth was likely too small to accommodate the suspected killer’s penis.

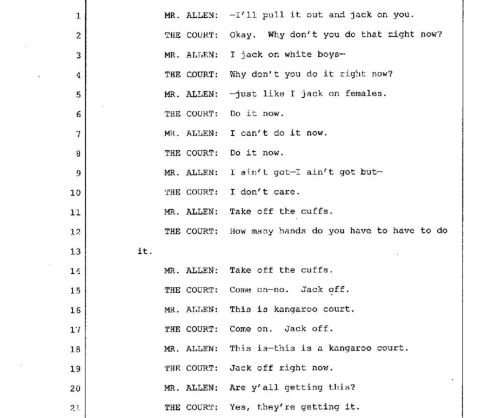

During one particularly surreal moment, Defendant Allen asked the court reporter if she was getting everything down after Judge Durham repeatedly dares Defendant Allen to jerk off right in the courtroom.

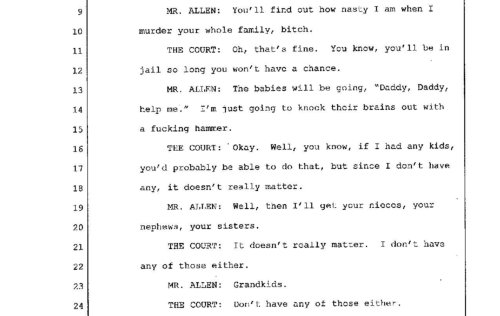

At this point, the Judge decides to tell defendant Allen that he has a “constitutional right to be a dumb-ass,” and that’s when Allen goes even further to the dark side and threatens to kill the judge, his whole family, and chop his children into bits.

THE TRANSCRIPT: While painfully homophobic at times and incredibly vulgar throughout, a complete reading of the entire 19 page comedy routine deserves a read. Check it out here.

THE COMIC-CON ANIMATED VIDEO: The above exchange between Judge Durham and Defendant Allen went viral and became an instant internet sensation. Judge Durham was nicknamed “Judge Fuckman Ass”, and Defendant Allen became “Donkey Dick Defendant”. What happened in court was so wildly unbelievable and yet somehow completely true, that the creator of the popular Adult Swim show “Rick & Morty” animated and voiced the entire transcript in character as Rick and Morty. The whole thing was premiered last month at the 2016 San Diego Comic-Con and received raving reviews. Click Here to watch the video clip.

JUDICIAL TRAINING: Although I’m sure Judge Durham is mortified at his new-found internet fame, the inescapable fact is that all judges, at some point in their judicial career, will face a defendant hell-bent on making a mockery of the proceedings. The only difference is the manner in which the presiding judge chooses to respond. My hope is that this blog post will serve as a training springboard and catalyst for judicial discussions on how to best answer the question that was asked at the beginnng of this post:

In order to maintain control in the courtroom and a sense of judicial dignity, at what point in the above exchange should the judge have STOPPED engaging the defendant, entered a finding of contempt and immediately ordered removal of defendant from the courtroom?

NOTE: By all accounts, other than this unfortunate incident, Judge Durham had a reputation as a well liked and respected jurist. In other words, if something like this can happened to a Judge Durham, then on any given bad day it could perhaps happen to you.

Alan F. Pendleton (Former District Court Judge)

alan.pendleton@mnlegalupdates.com

THE PROBLEM:

THE PROBLEM: