This educational series is sponsored by AutoGrabBag.com, a faith-based small business car accessory gift store.

Worcester v. Georgia, legal case in which the U.S. Supreme Court on March 3, 1832, held (5–1) that the states did not have the right to impose regulations on Native American land. Although Pres. Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the ruling, the decision helped form the basis for most subsequent law in the United States regarding Native Americans.

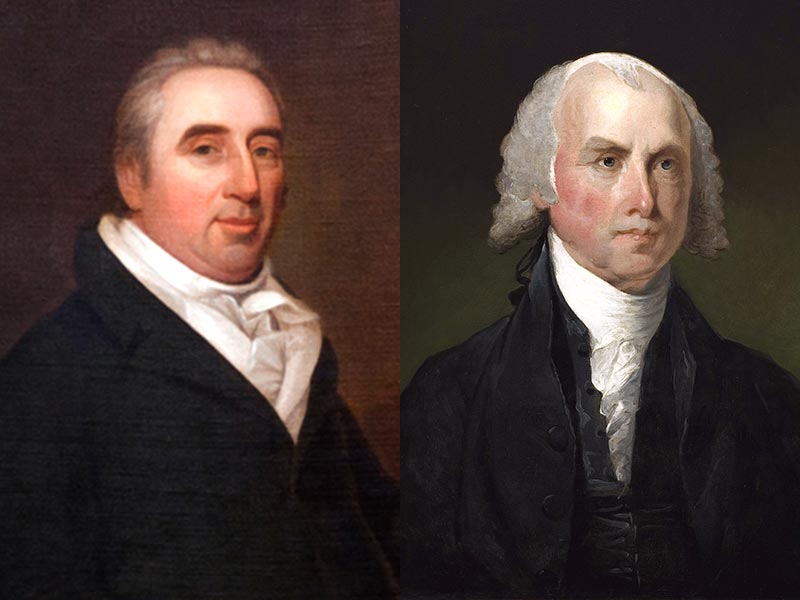

Worcester v. Georgia involved a group of white Christian missionaries, including Samuel A. Worcester, who were living in Cherokee territory in Georgia. In addition to their missionary work, the men were advising the Cherokee about resisting Georgia’s attempts to impose state laws on the Cherokee Nation, a self-governing nation whose independence and right to its land had been guaranteed in treaties with the United States government. In an effort to stop the missionaries, the state in 1830 passed an act that forbade “white persons” from living on Cherokee lands unless they obtained a license from the governor of Georgia and swore an oath of loyalty to the state. Worcester and the other missionaries had been invited by the Cherokee and were serving as missionaries under the authority of the U.S. federal government. They did not, however, have a license from Georgia, nor did they swear a loyalty oath to that state. Georgia state authorities arrested Worcester and several other missionaries. After they were convicted at trial in 1831 and sentenced to four years of hard labor in prison, Worcester appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Worcester argued that Georgia had no right to extend its laws to Cherokee territory. He contended that the act under which he had been convicted violated the U.S. Constitution, which gives to the U.S. Congress the authority to regulate commerce with Native Americans. The Constitution also bars the states from passing laws that alter the obligations of contracts—in this case, treaties. Several treaties between the Cherokee and the U.S. government recognized the independence and sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. Furthermore, Worcester argued that the Georgia laws violated an 1802 act of Congress that regulated trade and relations between the United States and the Indian tribes.

The Supreme Court agreed with Worcester, ruling 5 to 1 on March 3, 1832, that all the Georgia laws regarding the Cherokee Nation were unconstitutional and thus void. Writing for the court, Chief Justice John Marshall held that “the Indian nations had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights as the undisputed possessors of the soil.” Even though Native Americans were now under the protection of the United States, he wrote that “protection does not imply the destruction of the protected.” Marshall concluded:

The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory…in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with treaties and with the acts of Congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation, is, by our Constitution and laws, vested in the Government of the United States.

Georgia, however, ignored the decision, keeping Worcester and the other missionaries in prison. Eventually, they were granted a pardon and were released in 1833. Pres. Andrew Jackson declined to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision, thus allowing states to enact further legislation damaging to the tribes. The U.S. government began forcing the Cherokee off their land in 1838. In what became known as the Trail of Tears, some 15,000 Cherokee were driven from their land and were marched westward on a grueling journey that caused the deaths of some 4,000 of their people.

Worcester v. Georgia was a landmark case of the Supreme Court. Although it did not prevent the Cherokee from being removed from their land, the decision was often used to craft subsequent Indian law in the United States. The Worcester decision created an important precedent through which American Indians could, like states, reserve some areas of political autonomy.

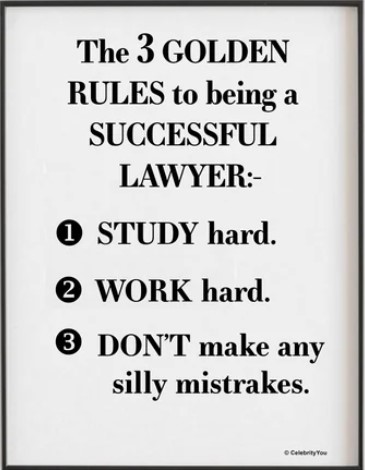

DISCLAIMER: These resources are created by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for educational purposes only. They may not reflect the current state of the law, and are not intended to provide legal advice, guidance on litigation, or commentary on any pending case or legislation.