BUT FIRST A NOTE ABOUT THE “JUDICIAL RESOURCE LIBRARY”: If you are getting this blog post via email please note that clicking on the above title (should be blue in the email) will take you to the blog website containing all past training updates and the “Judicial Resource Library”. The Judicial Resource Library is designed to be a simple one-click research site for judges and attorneys with hyperlinks to numerous legal research and reference sites, including but not limited to:

- State and Federal Legal Search Engines;

- Minnesota State Statutes;

- Rules of Criminal, Civil, Family & Juvenile Procedure;

- Rules of Evidence;

- General Rules of Practice (including all 10 titles);

- Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines;

- Attorney and Judicial Rules of Ethics;

- Payable List for Misdemeanor Offenses;

- The full text of the Minnesota and US Constitution;

- And, of course, all past Judicial Training Updates;

- Click on “Judicial Resource Library” to see if this site can help you.

FOR ATTORNEYS: If it’s your first trial or it’s been a while since you’ve tried a case, here’s a handy list of 10 steps to take when introducing your evidence at trial.

FOR JUDGES: The procedure for introducing evidence during trial is one of many topics that the presiding judge should discuss with both attorneys during the pretrial management conference.

STEP 1: Mark your exhibit for identification. The first step in offering an exhibit into evidence is to have it marked for purposes of identification. Once an exhibit is marked, it becomes part of the clerk’s record and can be designated as part of the record on appeal. When you should mark your exhibits varies from court to court? Traditionally the court clerk marked an exhibit when a witness was first to be asked about it. You’ve seen this on old TV shows: while the witness is on the stand, the attorney asks the clerk to mark the item “for purposes of identification,” and then everyone waits while the clerk places an identifying mark on the exhibit and logs it in the clerk’s record. This slow and dull process has led many judges to now require that exhibits be premarked, i.e., marked before trial begins or when court is not in session and before counsel begins questioning the witness. This issue should be addressed during the pretrial conference.

STEP 2: Show your exhibit to opposing counsel. Show the exhibit to opposing counsel when you ask that it be marked for identification. If the exhibit was premarked, show it to opposing counsel before you show it to the witness. This issue should be addressed during the pretrial conference.

STEP 3: Show your exhibit to the judge. If an exhibit was copied, hand the clerk both the original exhibit to be marked and a copy of the exhibit for the judge’s personal use. The process for providing a copy of the exhibit to the judge may differ depending on whether your trial is civil, criminal or family, etc. Many judges have personal preferences and different expectations when it comes to this issue. You need to know what those are.

STEP 4: Develop a factual basis for admitting your exhibit into evidence. In order to avoid the proverbial “Objection – lack of foundation”, use methods developed during pretrial preparation to establish the required factual basis supporting admission of the exhibit, e.g. ask the witness questions you’ve prepared for this purpose, ask the court to take judicial notice, rely on prior stipulations or perhaps requests for admissions if they provide the factual basis. Any anticipated admissibility problems should be discussed during the pretrial conference.

STEP 5: Offer your exhibit into evidence. Offer the exhibit into evidence immediately after laying the foundation for introducing it into evidence. It is not unusual for an attorney, after laying proper foundation, to forget to actually offer the exhibit into evidence. “Objection, counsel is asking questions about an item that is NOT in evidence.” It is usually a problem easily fixed but you may look inexperienced in the process. Any anticipated admissibility problems should be discussed during the pretrial conference.

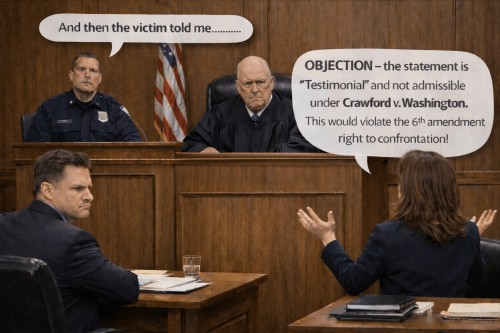

STEP 6: Anticipate and prepare for objections to admitting your evidence. Use an “evidence memo” or other pretrial preparation to show the court that the opposing party’s objection or claim of privilege is without merit. Anticipating objections or other admissibility problems and addressing them during the pretrial conference is critical to effective trial management.

STEP 7: Make an offer of proof. An offer of proof must be made to challenge on appeal a trial court’s exclusion of evidence. Minn. R. Evid. 103(a)(2). The only exception to this rule is if the substance of the excluded evidence is apparent from the context within which the question was asked. An offer of proof is a disclosure, made outside the hearing of the jury, of the substance, purpose, and relevance of evidence the offering party seeks to introduce. The legal reasons to make an offer of proof are threefold:

- To persuade the judge before a ruling is made to admit the evidence;

- To persuade the judge after a ruling is made to reconsider the ruling; and

- To create a record for appeal that the judge was specifically aware of the nature of the evidence being excluded.

I encourage you to read Training Update 15-02 titled: Evidentiary Rulings – Preserving the Record – 5 Rules every Judge (and Attorney) Must Know.

STEP 8: Obtain a definitive ruling on admissibility. It is not enough to object to evidence or to make an offer of proof. The court MUST make a definitive ruling and the parties have an absolute right to insist on a ruling. It is the responsibility of the party objecting to the evidence to make sure the judge actually rules on the objection. The party making an objection should also be sure that the court reporter is present when the ruling is made or, if not present, that the matter is placed on the record at a later point when the reporter is present. See Training Update 15-02. Failing to make a definitive ruling is usually a sign of judicial inexperience.

STEP 9: Disclose to the jury the substance of the admitted exhibit. Tell the jurors (thru testimony) about the exhibit admitted in evidence to make them aware of the exhibit’s meaning and importance. I have seen many occasions where following the receipt of an exhibit into evidence there was little or no follow up testimony regarding the exhibit leaving the jurors noticeably dissatisfied.

STEP 10: Verify the recorded admission of exhibits into evidence. Make certain that all proffered exhibits have been formally and unconditionally received into evidence and the clerk’s record reflects their receipt. Verify this by reviewing your exhibit log to ascertain whether the court has admitted all exhibits, comparing your exhibit log with the court clerk’s formal record. You can then re-offer any exhibit for which there is any question (and obtain a definitive ruling).

Note: Always double check to make sure that only properly admitted exhibits are taken back to the jury room for deliberations. I once ordered a mistrial following a verdict of guilty because a copy of the defendants criminal history printout somehow got mixed in with exhibits that went back to the jury room.

TOPIC FOR NEXT WEEKS TRAINING UPDATE – I will answer the following question:

QUESTION: In a jury trial how can you tell if your presiding judge is either inexperienced, incompetent or simply lazy?

Keep fighting for what you know is right.

Alan F. Pendleton (Former District Court Judge)

alan.pendleton@mnlegalupdates.com